Daleks and Nazis: Commentaries of History in Popular Culture

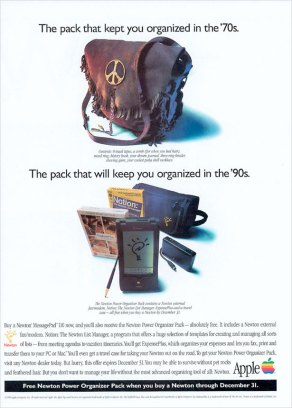

No piece of popular culture be it a film, television program, is created in a cognitive vacuum. Writers and composers are always influenced by the world around them. Countless critics and writers have drawn parallels to the post 9/11 world we live in as existing in recent superhero films such as The Dark Knight and Man of Steel. Such are examples of how recent history has influenced popular culture and in turn how popular culture has been used as a medium of commentary for contemporary events. This isn’t a recent phenomenon, however. In fact, if we take a look at a far more catastrophic event such as the Second World War, the commentary and public consensus is far stronger. Here we’ll examine public consensus in the decades following the Second World War and how this was portrayed through the popular television program Doctor Who.

Although the First World War definitely left its scars upon the world, most notably most of Europe, the Second World War was a completely different ball game. The wild card here was the Holocaust. Whilst the First World War had its fair share of atrocities and destruction, The Holocaust was another form of evil entirely. The Allied Film and Photography Unit (AFPU), a unit specifically trained for capturing the war on film was assigned to the various Allied forces that liberated the Concentration Camps at the end of the war. Although Nazi anti-Semitism was well known throughout Britain, viewers struggled to come to terms with such graphic and disturbing images of human suffering and cruelty as they made their way to British households through newspapers reporting on the atrocities. Of course, such images caused a stir and elicited feelings and opinions from various people.

It’s quite interesting to note that quite explicit imagery as taken from the concentration camps appears in the Doctor Who serial Genesis of the Daleks, broadcast two decades later. Genesis of the Daleks involved the Doctor travelling back in time to the very dawn of the Daleks creation. Let’s compare some images:

http://isurvived.org/Pictures_iSurvived-4/holocaust-corpses2.GIF

At first it seems a little difficult to see the similarities between the two, but let’s examine a little closely. In both cases the “Inferior” and “Unworthy” races have been purged, and are being disposed of callously by machinery operated by the “Superior Race” (In the case of the Daleks the “Superior race” exists within the machinery).

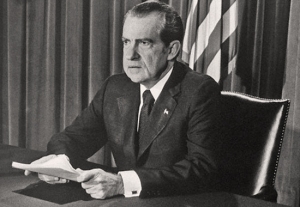

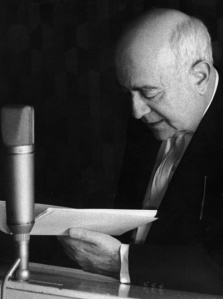

However, why do images taken from two decades prior find their way into Doctor Who, and thus, public consciousness two decades later? Interest and concern in the Holocaust actually dwindled in Britain and the United States by 1949 in favor of more pressing issues such as the Cold War as well as more preferred memories. Britain in particular preferred to focus on the more “heroic” aspects of the Second World War such as the bravery of the London Blitz, the Battle of Britain, the “Dam Buster”, and the escape from Colditz prison. However, events and efforts surrounding the capture and prosecution of Nazi war criminals in Europe brought these issues back to public consciousness. The most notable of these was the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1960-1961. Although the trial took place in Israel, it was broadcasted globally, and brought the Holocaust back to public consciousness. Tim Cole actually argues that this was one of the key ingredients to creating the Holocaust “Myth” (meaning the way the Holocaust is remembered, rather than suggesting that it never occurred). Of greater significance is that it gave this generation, some of whom would have been born during or after the Second World War, a face to which they could pin the past atrocities on. Again, this is reminiscent in Genesis of the Daleks in the form of Nyder, who portrays a cold professionalism in keeping the Kaled race “pure” reminiscent with Nazi Concentration Camp commanders. The physical similarities between Nyder and Henrich Himmler, a key Nazi Concentration Camp Mastermind are also quite deliberate:

http://static2.wikia.nocookie.net/__cb20101214215860/tardis/images/8/87/Kaleds.jpg

Of particular interest is the motivations behind the creation of the story as well as the reactions from the general public and it’s consistency with the reception of a Holocaust exhibition held in Coventry. Both Dr. Walter Deveen, convener of the exhibition, and Phillip Hinchcliffe and Terry Nation stated that the intention of the exhibition and Genesis of the Daleks was to educate the younger generation as to past atrocities and the dangers of Fascism. Both also received similar responses. Some praised both works for presenting realistic and respectful portrayals and messages regarding the atrocity. Others were highly critical, Canon Hedley Hodkin criticizing the exhibition for being nothing more than excessive sadism, and Mary Whitehouse, a campaigner for appropriate television viewing for youths criticized the serial for its violent content and realistic portrayals of trench warfare. Several school groups were also banned from attending the exhibition.

Events are easy to learn about and evaluate. However, uncovering feelings and opinions of the past of such events is somewhat harder to do. This is why popular culture is so useful. As popular culture is consumed by the vast majority, its popularity, viewership, and reception can be useful tools in analyzing past opinions and reactions.

Bibliography: Caven, H. “Horror in our Time: Images of the Concentration Camps in the British Media, 1945” Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2001.

Chapman, James. Inside the TARDIS: The Worlds of Doctor Who (London, I.B. Tauris, 2006)

Tim Cole, Selling the Holocaust: From Auschwitz to Schindler, How History is Bought, Packaged, and Sold (New York, Routledge, 1999).

Doctor Who: Genesis of the Daleks [DVD], director: D. Maloney, British Broadcasting Corporation, 1975.

Struck, Janina. Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence (I.B. Tauris, New York, 2005).

Doctor Who: Genesis of the Daleks Part 6: http://images3.wikia.nocookie.net/__cb20101106152439/headhuntersholosuite/images/3/37/Doctor_Who_-_Genesis_of_the_Daleks_(Part_6)_005.jpg

Holocaust Survivors Network: http://isurvived.org/Pictures_iSurvived-4/holocaust-corpses2.GIF

Kaleds http://static2.wikia.nocookie.net/__cb20101214215860/tardis/images/8/87/Kaleds.jpg