Australia during the 19th century has been renowned as one of the most democratically experimental environments to have ever existed. In comparison to our British forefathers, the Australian colonies were achieving great levels of success when it came to eliminating the barriers of class and distinction that were such a defining feature of the old country. During the 1850′s, NSW, Victoria, South Australia and Queensland had all achieved the right for men to vote, giving the impression that these colonies had the makings to shape up as experimental hot spots for liberal development.

Romantic memories of convict Australia certainly have become popular since the latter half of the 20th century, as many historians have attempted to explain what it is that defines our “Australian” character. It is quite easy to envisage transported felons as the founding fathers of what was considered to be an anti-authoritarian ethos, which separated us from British culture… Picture a colonial Australia where convicts and ex-convicts wandered independently from station to station, not bound to one employer, often only known by a nickname, and not needing reference to land a job. This sort of frontier depiction has been a popular one amongst the earlier works of some Australian historians (Reynolds, 1969).

However, there is another side of the story which does not fit into what some would describe as our national narrative. Instead this is the history of a somewhat unlikely working class hero who emerged out of the political dissatisfaction that was occurring in Britain during the 1840′s. He was not a horse riding, gun wielding bush ranger. On the contrary he was a 4’11 tailor named William Cuffay, who had been transported to Australia on an account of sedition. Unlike the some of the other mythological heroes of Australian folklore, Cuffay was black, suffered a spinal deformation and was 60 years of age when he was transported to Van Diemen’s Land. Although these contextual disadvantages may have limited the political options for some, Cuffay went on to become some what of a celebrity within the Tasmanian media over the next 20 years of his life.

This project has aimed to describe the relationship between Cuffay’s political life, thought and practices – and his representation in colonial journals, regarding the Master and Servant Act. The act in question has been found to be one of the most draconian pieces of legislation in Australia’s short history. Imagine if in the present, day you were able to be sentenced as a criminal for any “misconduct” or breach of contract within the work place. If you were to show up late to your shift, perform your duties to a lower standard or swear at your boss (heaven forbid) you would be thrown into solitary confinement for thirty days, fined an amount that was impossible to pay back or even given a three month charge of imprisonment with hard labour on the side. Additionally, you would be required to go back to your place of employment after the sentencing and complete your contract. This was a likely occurrence for “misbehaving” workers in V.D.L during the 1850′s, as justice moved swiftly with the requirement of only one magistrate to seal your fate. The Master and Servant Act, and its various amendments is the piece of legislation which sets our political context and provides the foundation for a furious debate, occurring between Cuffay and the various media outlets of Tasmania during the 1850′s.

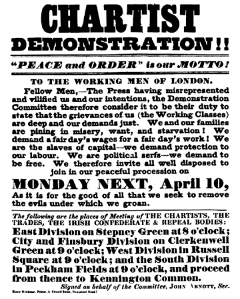

What has been found from this inquiry into the past is that Cuffay was not popular amongst his established contemporary’s. As debate raged over the various amendments that occurred throughout the era, there transpired a vitriolic and consistent class based disdain from the colonial media outlets, for the man who was an unlikely champion of the working class. Cuffay was clearly applying the tactics he had learned and mastered with the Chartist’s back in the UK. He was reported as the chair man of monster meetings (a common Chartist ploy) in iconic locations such as the Albert Theater in Hobart, and was clearly having an affect on the rousing of an emerging working class movement that opposed the draconian features of a dated Master and Servant Act.

Cuffays political life, thought and practices had effectively disrupted not only Tasmanian journals, but even elicited a response from some of the largest papers in Sydney by 1857. Although it wasn’t until he had openly ridiculed the media that he started to receive negative attention from various outlets, the class based rhetoric saturated throughout each article there after, reveals Cuffay as a character that was willing to fight against established institutions of power even though he was disadvantaged by age, race and physical condition. Such was the status of Cuffay, that when he finally passed away in 1870, his obituary was published in three states (Tasmania, Victoria and NSW). There is no singular grave marked site for Cuffay, however, it is likely that he was buried in a mass grave amongst the Trinity Burial Ground in Tasmania. Cuffay’s limited mention in our national narrative of liberal development and convict defiance make him some what of an unlikely hero who contributed with what he could to the working class movement throughout the 19th century.

Bibliography and Further Reading:

Coghlan, T.A. Labour and Industry in Australia (1918) Vol. 2

Davidson, A.P. “A Skeleton in the Cupboard: Master and Servant Legislation and the Industrial Torts in Tasmania”, University of Tasmania Law Review, Feb 1976 Vol. 5(2)

Gossman, N. ‘William Cuffay: London’s Black Chartist’, Phylon, vol. 44, no. 1, 1983

Jones, David. Chartism and the Chartists, Allan Lane, London

Patmore, G. “A Workingman’s Paradise? Labour 1850-91.” Australian Labour History. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire, 1991

Pickering, P. “A Lesson Lost? Chartism and Australian Democracy.” Agora, Vol. 46, no. 4, 2011

Reynolds, H. ‘“That Hated Stain”: The Aftermath of Transportation in Tasmania’, Historical Studies, Vol. 14, no. 53, 1969

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/cuffay_william.shtml Accessed 13/11/14

This is such an awesome and unique research topic! I feel as though researching Cuffay’s life would have required a hefty amount of primary research. When you were trawling through things did you ever come across anyone who followed a similar path to Cuffay or would you say that his situation and his politically active life were unique in Van Diemen’s Land? I think the way you wrote this blog and your project as a whole really highlights how Cuffay’s experience differs from our typical understanding of colonial life in Australia and Australian History in general. Awesome work!